|

There were always rumours circulating about tunnels under Cane Hill. These stories were well entrenched when I made my first furtive incursions into the hospital buildings and we were pleased to eventually discover a large tunnel system under the hospital itself. Was the mystery now solved? No, it wasn’t. The rumour persisted and its basis wasn't revealed until the unconnected Deep Shelter at the foot of hill was more widely explored. This essay was the first of serial historical features for Coulsdon's local listing magazine CR5. It was partly a straight retelling of the former World War Two shelter and also an examination of how local rumours are sown and germinate – an effect amplified by the proximity of Cane Hill which bred superstition and gossip.

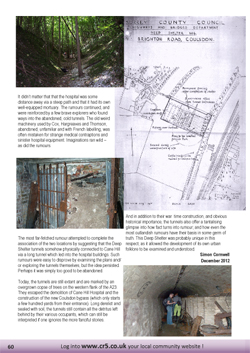

One of the problems the historian faces is how to separate fact from fiction. In fact, the separation may not be as black-and-white as that, as stories can spring from original facts, amplified by years of assumptions, half-truths and Chinese whispers. This is especially true of underground works, tunnels and all manner of subterranean artefacts; their existence, or even rumoured existence, can lead to wild tales and rumours circulating, with their extents, former function and current condition being subject to much gossip. In this respect, the tunnel system constructed at the foot of Cane Hill ticks all the rumour mill boxes with gusto. Much has been discussed and written about these tunnels over the years and they have gained an almost legendary status around the area; yet these tunnels are also a perfect example of how these urban legends begin and how they become exaggerated. For these tunnels, located in a small forgotten wood alongside the A23, were either a nuclear bomb shelter, the Cane Hill mortuary or a secret medical testing facility. None of these fanciful or frightful rumours was true, but it is possible to determine how they came about. The inception of this network of brick-lined tunnels was prompted by war-time necessity. Either during, or slightly before the Second World War, Surrey Council drew up plans for at least four "Deep Shelters." A plan from their Highways and Bridges department revealed that the "Brighton Road, Coulsdon" shelter was the fourth, located on the western side of the A23, and positioned to be within easy reach of the houses across the road. The planned layout of the Brighton Road tunnels was simple and functional. Three parallel longitudinal tunnels of about 200 feet in length were to be driven into the chalk hillside, with four parallel lateral tunnels connecting them. Spoil was to be piled onto the hill above the tunnels to provide extra protection from bombing, whilst more soil was heaped in front of the three tunnel entrances to form a blast wall. Three additional offset entrances then connected the blast wall entrances to the car park adjoining the A23. There was little in the plans to determine the function of each of the tunnels, but the laterals inside the entrance were dug as latrines and some small separate spurs were labelled "sick bay" and "canteen." The plan was over ambitious and only a fraction of the intended tunnels were built. Two of the longitudinal tunnels were abandoned, stopping short in a sheer white wall of chalk whilst only two lateral tunnels were completed. A mysterious new room was dug to the north of the tunnels – not shown on the plans – whilst the canteen was never excavated. Perhaps budgetary constraints prevented them from being fully realised as the total cost of all four shelters was given as £71,000 in 1943. The wartime use of these shelters was also in dispute. Whilst it wasn’t in any doubt that these were public shelters, rumours circulated that the Canadian Military used for the tunnels for storage. Given that the saturation bombing expected didn't hit Croydon and Coulsdon, and that most householders had their own shelters, then perhaps the tunnels were found to be poorly used and therefore available for other uses. After the cessation of hostilities, the various bunkers and shelters (now owned by the London County Council) were mothballed but several were reconsidered as potential nuclear shelters as the Cold War began to take hold. Surrey County Council resurveyed the Brighton Road tunnels and reported that they were again considered useful. As such, they were never used or refurbished as nuclear shelters, but this consideration was enough to start some gossip and so the rumours began. London County Council was therefore probably relieved when Cox, Hargreaves and Thomson Limited approached them with an offer for the unused tunnels. The firm manufactured lenses for telescopes and required a location which had constant temperature (so that the glass would not expand and contract whilst being ground and polished) and long rooms (where the focussing of the lenses could be tested). The tunnels appeared ideal. The company made several small changes to the layout of the tunnels after taking over in 1949. The southern entrance was bricked up, the central tunnel was extended out to the car park, and the northern tunnel had its dog leg removed so it exited straight out into the valley behind the blast wall. The "sick bay" required attention and was fitted with a new concrete skin, the tunnels were completely rewired and the firm took delivery of custom French machines which were used as the lens grinders. Whilst the tunnels were well suited for the production of extremely high quality lenses, they took their toll on the workforce and equipment. It was very cold and damp – water would condense in the electrical conduits causing the power to regularly short out. Obviously annoyed by these constant electrical brown-outs and the subsequent risk of shock trying to repair the sodden fuses, the company rewired a fridge to act as an air condenser that dripped water into a bucket and which required periodic emptying. Such problems were not evident when the firm was the subject of a British Pathe news feature. The short programme concentrated on the company's unique manufacturing skills and their equally unique premises. The film started with an employee taking a rough, unfinished lens from the car park into the tunnels – a barren view and completely unrecognisable to the choked woodland of today. But working in the cold and damp conditions of the shelter was simply asking too much and the optical works left the tunnels in the 1970s. Employee Norman Fisher last visited the bunker in 1975-6 and found the lights inoperative, the door partially jammed and the machines broken. Cox, Hargreaves and Thomson Limited was wound up on the 12th October 1978 after almost thirty years in the tunnels. It seems that a garage or workshop then took over and used the southern longitudinal tunnel. New partitions and tool racks were installed and were soon populated with components, body parts and engines. Given the number of garages and repair units on the eastern side of the A23, then it’s not unlikely that an enterprising garage owner took on the tunnels as an extension to his business. But the same problems which dogged Cox, Hargreaves and Thomson probably plagued the garage workers. It was cold and wet and everything brought down into the tunnels would start to rust. It was not an ideal environment and soon the semi-derelict tunnels were being used as a dump. Tractor wheels, a wooden telephone box and even a railway semaphore were hauled into the southern longitudinal tunnel before the whole complex was swiftly sealed by bulldozing huge banks of soil through the three tunnel entrances. And so they were left and the whole area quickly became overgrown and unkempt. The story should've concluded after the backfilling of the tunnel entrances in the 1980s. Deemed surplus to requirements, partially filled with industrial rubbish, and now too remote, overgrown and damp to be of use, Deep Shelter No. 4 should’ve been confined to the footnotes of history. But it was the near presence of Cane Hill Hospital that prompted the sinister, alternative history of the tunnels. Without Cane Hill the tunnels would’ve been a mostly-forgotten curio filled with obscure junk, but the hospital ensured that the tunnels became somehow connected with the institution and the obscure rusting machinery inside took on sinister new overtones, driven by the superstition surrounding the complex. So, stories began to circulate connecting the two. The tunnels became associated with the hospital, either becoming the mortuary or some weird laboratory where all manner of strange experiments took place. It didn’t matter that that the hospital was some distance away via a steep path and that it had its own well-equipped mortuary. The rumours continued, and were reinforced by a few brave explorers who found ways into the abandoned, cold tunnels. The old weird machinery used by Cox, Hargreaves and Thomson, abandoned, unfamiliar and with French labelling, was often mistaken for strange medical contraptions and sinister hospital equipment. Imaginations ran wild – as did the rumours. The most far-fetched rumour attempted to complete the association of the two locations by suggesting that the Deep Shelter tunnels somehow physically connected to Cane Hill via a long tunnel which led into the hospital buildings. Such rumours were easy to disprove by examining the plans and/or exploring the tunnels themselves, but the idea persisted. Perhaps it was simply too good to be abandoned. Today, the tunnels are still extant and are marked by an overgrown copse of trees on the western flank of the A23. They escaped the demolition of Cane Hill Hospital and the construction of the new Coulsdon bypass (which only starts a few hundred yards from their entrance). Long derelict and sealed with soil, the tunnels still contain all the detritus left behind by their various occupants, which can still be interpreted if one ignores the more fanciful stories. And in addition to their war time construction, and obvious historical importance, the tunnels also offer a tantalising glimpse into how fact turns into rumour; and how even the most outlandish rumours have their basis in some germ of truth. This Deep Shelter was probably unique in this respect, as it allowed the development of its own urban folklore to be examined and understood. Simon Cornwell

Return to Brighton Road Shelter (Cane Hill Bunker)

|